Old Master's Never Forget

Bear with me, this happened some time ago, some details are fuzzy and the chat logs are gone, so parts will just have to be from memory.

Back in May, we had the worst possible scenario occur with one of our largest Elasticsearch clusters; The total deletion of the entire cluster’s worth of data.

Does this look right to you?

I remember the initial discovery because it was a Friday, I was of course playing competitive in Overwatch. My coworker got paged that the cluster had gone red for over a period of 30 minutes. Soon after I get a message from him along the lines of:

Hey, can you take a look at this? Does this look right to you? 22k unassigned shards, 0% active primaries.

Stunned, still playing my game, I replied I could take a look after I finish (lose) my game. Eventually I busted out my laptop, hopped on and took a look for myself.

It didn’t take long to confirm, but the entire cluster somehow had lost all of its data. Reading the output of _cat/indices gave us a startling realization. All of the indices were from one to three months ago.

Three months ago? That made no sense, we close indices at the one month mark, then delete them entirely after 45 days. To double confirm the data loss I hopped over to a couple random nodes and spot checked the storage paths. They were indeed empty. The data loss and the report from _cat/allocation was completely true.

What was still a mystery was where the older indices came from, they do not exist on disk in any data node. Checking _cat/nodes looked normal, except, one node’s naming convention was familiar, but different.

xxx.xxx.xx.xxx 23 98 1 0.53 0.84 0.72 mi - cluster_master01-es01

xxx.xxx.xx.xxx 13 98 3 1.50 0.98 1.02 mi * cluster-master01-es06

xxx.xxx.xx.xxx 44 96 2 0.63 0.81 0.92 mi - cluster_master02-es02

xxx.xxx.xx.xxx 30 93 2 0.54 0.95 0.94 mi - cluster_master03-es03

xxx.xxx.xx.xxx 21 95 3 1.29 1.13 0.92 mi - cluster_master04-es04

xxx.xxx.xx.xxx 35 94 3 0.57 0.95 1.02 mi - cluster_master05-es05

Something similar to what we saw that Friday night

Generally we name master nodes in the way of <cluster_name>_master<num>-<machine_num> (for example, cluster_master01-es01), prior the convention was exactly the same, except the separator between the cluster name and node type was a single dash -1. Previously, this cluster’s master nodes existed on the same hosts that data nodes resided on. During an upgrade we migrated these nodes to a separate pool of hosts dedicated just for master nodes.

Hopping onto the older node revealed it was one that was decommissioned the previous month. Its systemd service hadn’t been disabled nor had its storage been cleared during decommissioning.

How it started was a bit of luck. During a hardware maintenance the machine was rebooted. Unknown to us the old master’s service started with its state from a month ago still on disk. It silently waited until that Friday night, at which point it was promoted to master.

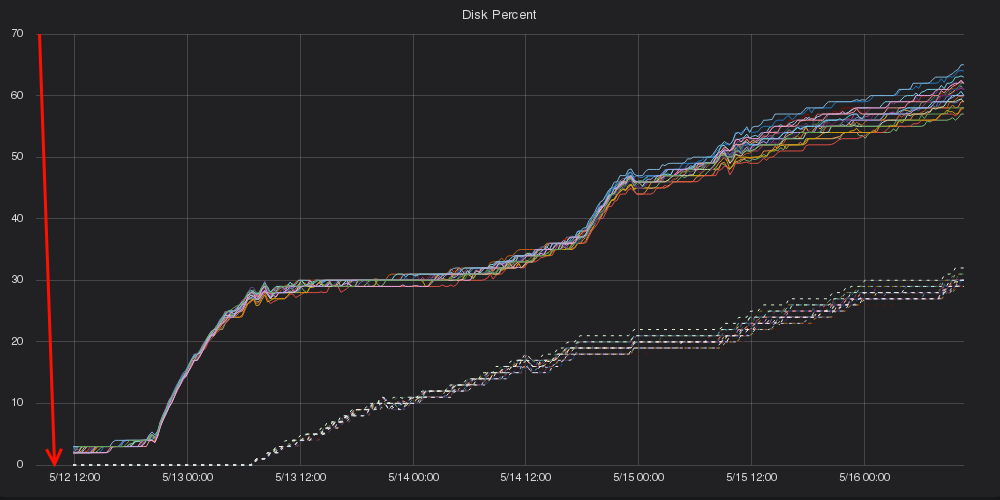

Promptly after being promoted, all data was deleted. The graphs were jarring; in Grafana just before the deletion you can see a healthy 130TB (replicated) floating around. Within a minute of the new master taking charge, that 130TB went to zip, zero, nada, absolutely nothing.

This isn’t the fresh start I imagined

An entire 45 days worth of data was gone in an instant due to one, single old master.

Let’s just restore it

Talking with the team that utilized the cluster, they made it clear they could operate with as little as two weeks worth, but the full month is obviously preferable.

Thankfully, in some odd, cosmically funny way, that Wednesday I took a full backup of the cluster, miraculously, the entire backup finished Thursday afternoon with less than 1% failed shards (due to time outs). Checking the snapshot, it looked like we had up to a full month of data, awesome!

So without further ado I sent off a request, the recovery started. All is well right? Unfortunately, it’s not that easy.

Soon after starting the restore we ran into issues. Many, many failed shards, tons of time outs, what was wrong? At this point I couldn’t make heads or tails of the issue, there was no apparent issue with Ceph or the cluster. Adjusting the bandwidth rates, chunk sizes, netted me no extra benefit.

Eventually what worked was narrowing the scope of the backup to a single day at a time. Creating a new repository with higher bandwidth limits per node I used this to restore a single day at a time, watching for time outs and deleting any indices that had any failed shards. Those I would restore separately after the remaining indices for the day finished.

Hopping onto one of the master nodes I got a couple terminals setup. One with a giant status so I could see it from my bed, another continuously putting the backup in a loop to ensure it would start. Every two to three hours a day would restore, I’d get up, start the next one, go back to bed. If the backup had issues restoring some indices or shards, I’d have to wipe the index they’re related to, restore just those, and continue which could add another hour to the already two to three hour restore.

Swapping out with my coworker once in the mornings so I could get some sleep. We continued this process into Monday morning, by then we had about three weeks worth of data restored and accessible.

That wasn’t the most fun weekend

My coworker in the meanwhile had pulled down the most recent days’ worth of data from Ceph that we archive separately and used Logstash to backfill the missing days between the backup’s latest data and the current time. This was a slow, very slow process, but it worked.

Eventually we managed to restore an entire month’s worth of data by Tuesday. Everything looked good, the old master had its configuration, storage, and service files obliterated. Paranoid we scoured the other hosts in the pool and confirmed the older masters were completely gone.

Lessons learned

We learned much from this, and in an odd way this was the perfect storm. We had the perfect combination of the only old master with its configuration and storage still lying around getting rebooted. We had a snapshot handy and I had just finished writing the tool and documentation for a little tool to decommission nodes/clusters for us.

To get down to it though, we learned that our methodology for restoring and backfilling had some serious problems. The infrastructure and configuration also had some problems that needed tweaked.

1. Restoring a full snapshot wasn’t feasible

It turns out the nginx configuration for the load balancers, as part of our default nginx configuration we cache objects over a specified size. As a result, when ES is reaching out for thousands of objects gigabytes in size, most of these objects are immediately written to disk from memory and passed off.

Not only is it thrashing the root SSD for the LBs, but if it can’t fetch it fast enough and write it to disk (only for it to be immediately thrown out) it would cause a ES to timeout on fetching the object. Adjusting that helped immensely with our ability to restore larger amounts of data.

There’s still time outs due to how many objects ES is requesting, and with no way to limit the number of shards, indices, or chunks it tries to fetch at any given time there’s a real risk in DDoSing the LBs with larger clusters like this one.

2. Snapshotting the entire cluster isn’t feasible

Unfortunately, at least for this cluster we had to hop off the Ceph storage, for ES it just has too many hiccups, takes too long and puts a strain on the LBs any time the cluster needs to dump. We’ve tried a couple various solutions, even chunking snapshot jobs based on shard counts to split one daily index into N chunks to make restoring and snapshotting less of a fragile procedure.2

Eventually we opted to setup a GCS bucket. It works, and although we nearly max out the bandwidth to the bucket (which causes other issues, go figure, and better yet, no way to establish a bandwidth limit at the plugin level) we can complete snapshot for the previous days’ worth of indices in under 3-4 hours.

Setup is still a pain as it is managed entirely through the keystore manager, which I guess is fine if your cluster is small, or made with it in mind. With a larger 50+ node cluster it quickly becomes a pain. Thankfully with some python and paramiko that problem went away.

To avoid complications with taking a full backup, we instead snapshot the previous days data once every day. The current days data can be backfilled from ceph with the entire contents restored wholesale from GCS.

3. Backfilling with Logstash was incredibly slow

After that week I spent some time working on a new backfill strategy centered around Filebeat. Instead to backfill we now use a utility that:

- Checks the S3 (in Ceph) bucket for any objects that match one or more regex patterns.

- For example, we can match down to a particular hour for an individual index due to how the objects are named in each bucket.

- Dumps these individual objects in “buckets” with a cap of 2GB (uncompressed this is generally ~14GB of data). The idea being each set of objects will be its own job.

- From a skeleton chart it will spit out a set of Helm/Kubernetes resources ready for deployment that:

- Provisions a new PVC for each new “bucket” of objects.

- Creates an individual job responsible for each bucket.

- Supplies the configmaps for s3cmd and Filebeat.

- Once launched each individual job (if there’s spare capacity, otherwise they’ll hang around until jobs finish and resources free up):

- Downloads its list of objects from the bucket and only those objects.

- Decompresses them.

- Starts Filebeat with our supplied configmap.

- Indexes to completion and exits.

Two catches though.

One is you’ll need to manually clean up the PVCs as they’re made with the retain policy. I did this to ensure the buckets don’t need to be remade if any single job has issues grabbing its files. Cleaning them up is as simple as kubectl -n something delete pvc -l app=es-backfill anyway, so no harm there.

Secondly, this is limited to the namespaces and nodes with the Ceph RBDs available, which might be a small subset of the total available nodes. So although we may have plenty of machines available we’re limited to less than a handful for scheduling. This means if we have 65 jobs to launch, we might have to settle for 30 at any given time. However we’re limited by how many ES nodes we can hit anyhow (and how active their respective bulk thread pools are).

This method is able to backfill the same day period in generally less than a few hours, a huge improvement over the sluggish, hands-on day long indexing that Logstash struggled through. Granted, we could have spent more time configuring Logstash for this purpose, but Filebeat was simpler, we only needed to index already processed documents, and preferably perform well even at low memory limits.3

Aside from the ugly invocation to create the job, it works. There’s probably a better way, but for now, this suits us as we generally only backfill gaps occasionally.

4. Decommissioning needs to be standardized

As mentioned, the same week the cluster decided to delete itself was the same week I had just finished a tool that would decommission entire clusters for us. Due to the weirdness that we encountered I added the ability to pick individual hosts and nodes.

Then the ability to seek out and find any/all nodes that were not attached to any active clusters, giving the user the ability to search and destroy any leftover nodes.

The documentation around this was improved, and rewritten to demonstrate the new processes. I also took the chance to scour our pools of ES hosts of any derelict nodes, destroying them and lowering the risk of this happening again.

-

We try to keep the names standardized like this as it makes scripts/Rundeck jobs easier to automate if they’re all labelled consistently. ↩

-

This partly worked, but Ceph still remains an issue. Just due to the sheer size of the cluster and amount of data it quickly congests the LBs for Ceph, so no matter what method we tried we’d never get a clean backup unfortunately. Failed shards were an inevitability, not a rare occurrence. ↩

-

For reference, each backfill job gets 1-4 CPU requested, and has a default request of 2GB, up to 10GB limit. ↩